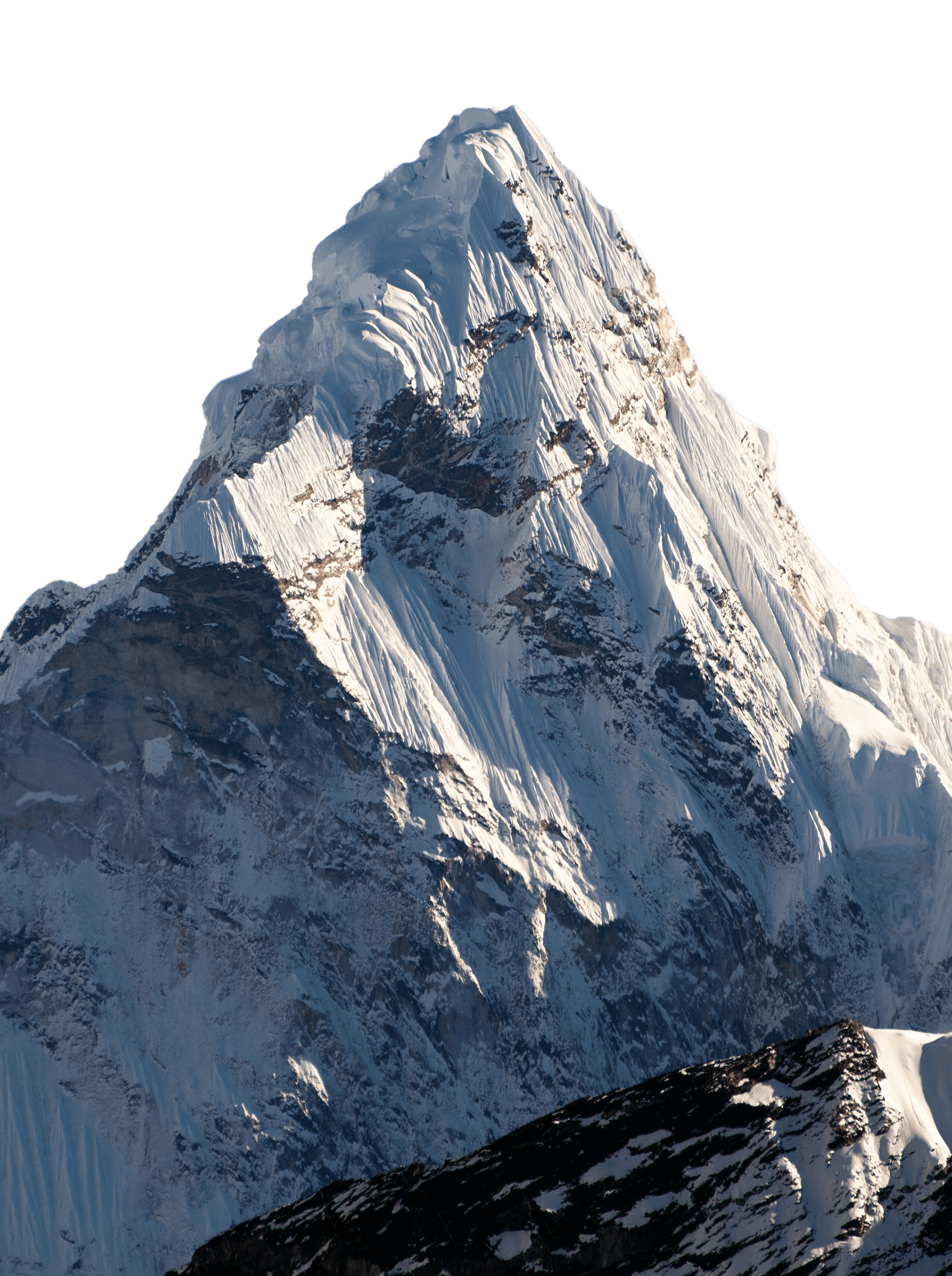

A National Crisis: The Treacherous Mountain of Millennial Student Debt

Neil tried to follow in the footsteps of his father, also a lawyer. But he ended up with far more debt than he had originally anticipated – $150,000 upon graduating.

And though he was diligent in making at least the minimum payment each month, Neil’s debt ballooned to $200,000 just years later.

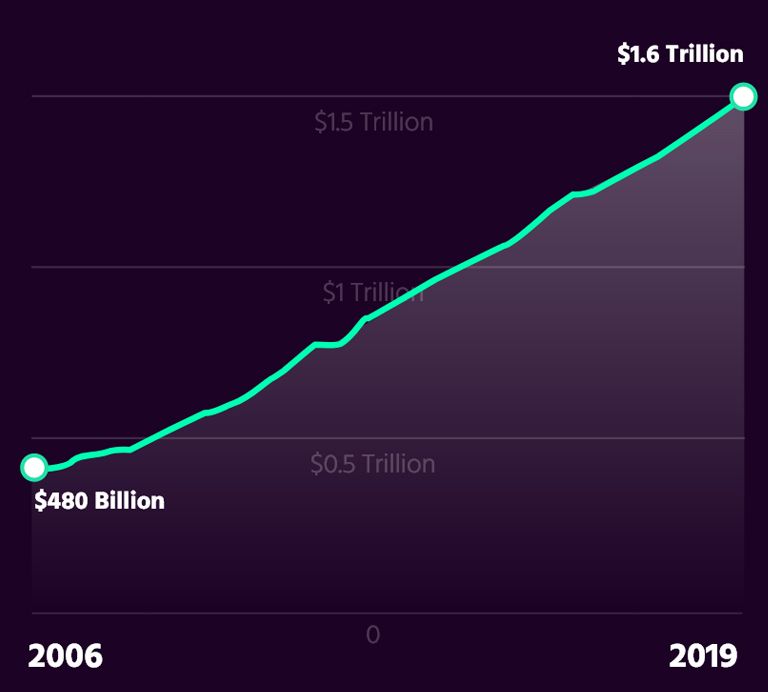

Neil is one of the nearly 45 million Americans struggling to pay off a student loan balance. While our collective educational debt has passed the $1.6 trillion mark, this burden isn’t distributed equally among Americans.

Millennials like Neil hold the largest share of student loan debt. They owe, on average, more than $18,000. In contrast, when Generation X was finishing their studies, they had a 2004 median student loan balance of just $13,000.

What we found was shocking.

Looking back, do you think that your college degree is worth the amount you paid in tuition?

A small but notable group (7.29%) said they don’t expect to be able to pay off their student loan debt before they die.

Despite the inclusion of student loan debt in our national

zeitgeist, it continues to pile up, mountain by mountain, for

the millions of Americans suffering under the weight of a

broken system.

Ultimately, there is little else for the educationally indebted

to do but make their monthly payments, all the while

sharing in Neil’s hope that somebody, someday, will fix it.

The Growing Student Debt Crisis: A Mountain out of a Molehill

Student loan debt hasn’t always been an existential and financial burden, nor a national crisis.

While I was researching this article, I talked to my parents about their own experiences paying for law school – which they attended in the late 1970s/early 1980s.

They went to a state school, West Virginia University, where the annual law school tuition was “under $5,000” as they recall.

Paying for a graduate degree was such a non-issue that my dad doesn’t even remember if the small student loan he took out was for tuition or textbooks.

Whatever it was, the interest rate was low, and they paid the loan back within a few years.

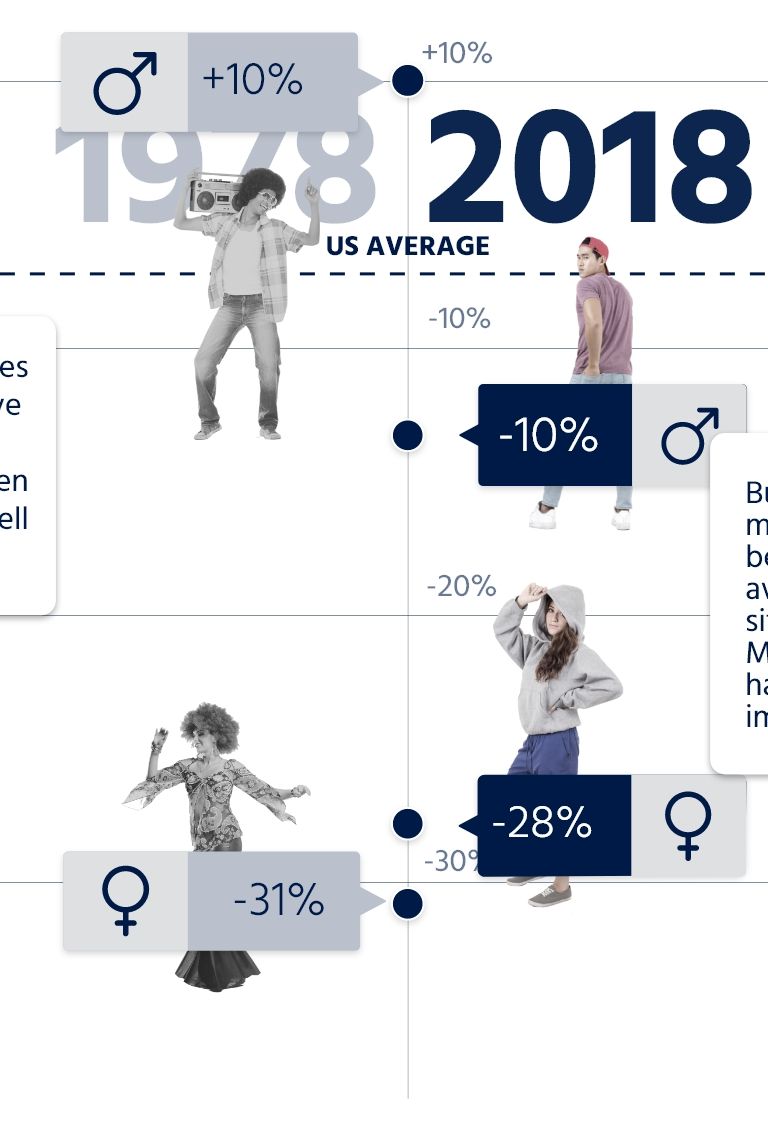

My Baby Boomer parents aren’t the only generation that could prioritize personal interests and public service above high salaries. When Generation X threw its collective graduation cap into the air, “finding yourself” was still a bigger priority than figuring out how many jobs you needed to hold in order to make your monthly loan payments.

But no longer.

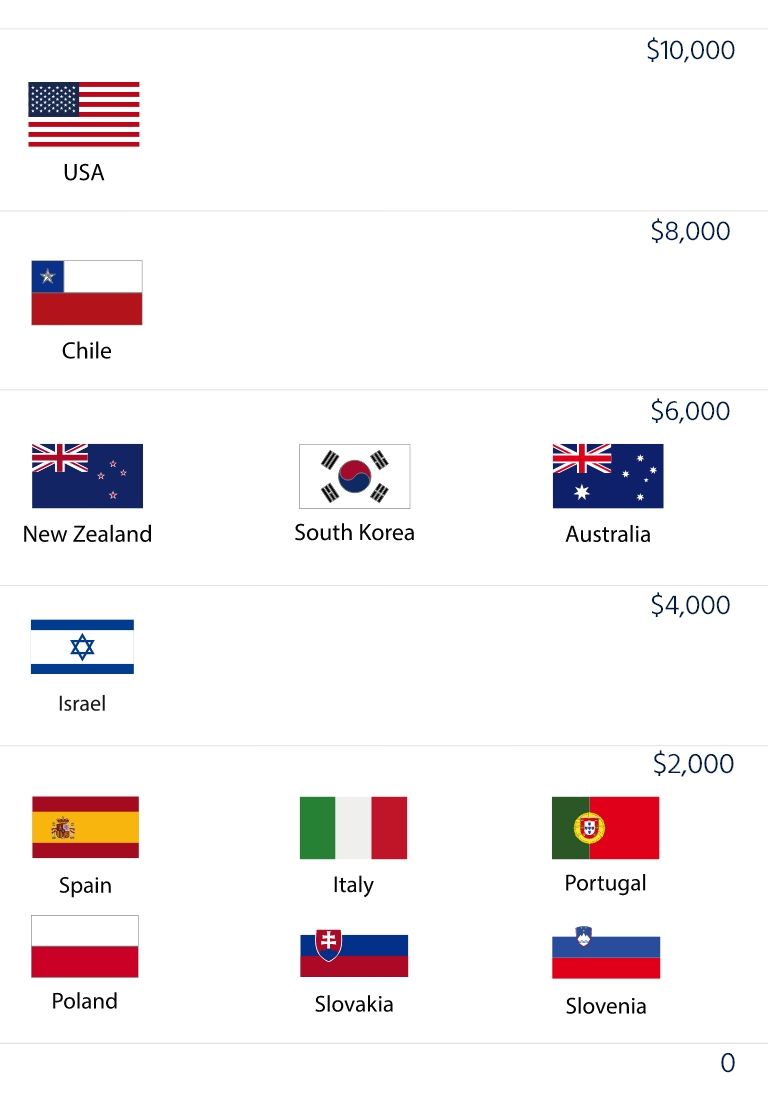

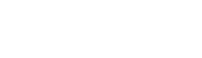

Private tuition has more than doubled on average since the late 1980s, now approaching $35,000 per year. And public tuition has more than tripled, nearing $10,000 today.

Keep in mind that these averages only represent tuition costs, not all of the other expenses such as textbooks, food, and housing that students also must cover.

Over recent years, the average cost of tuition has skyrocketed

Tuition Cost

Source: Trends in College Pricing 2017, Collegeboard.org

There has been a corresponding rise in student debt

Student Debt

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

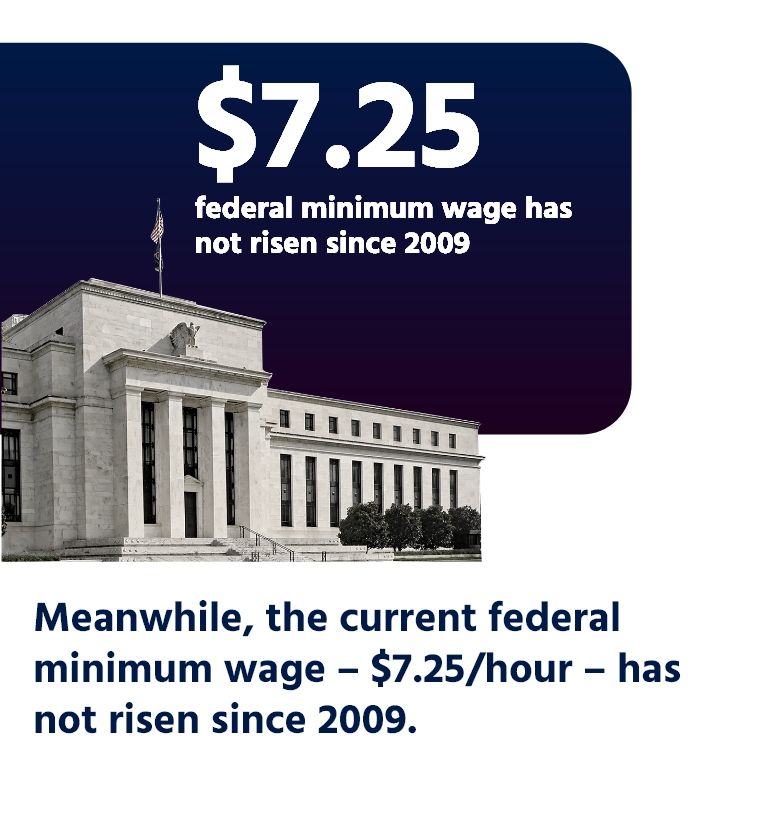

Meanwhile, the current federal minimum wage – $7.25/hour – has not risen since 2009.

In 1990, it was $3.80. Thus, a person in 1990 would have needed to work about 839 hours at minimum wage to pay for a year’s tuition at a state school.

Today, it would be 1,379 hours.

And this, of course, is why it’s so hard and, in some cases impossible, to pay your way through college now.

Jennifer, 39, grew up on a farm in North Dakota with parents who encouraged her to attend college but couldn’t help her pay for it. “It was definitely a pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps mentality,” she said.

“I was probably the most serious freshman student you’ll ever see, because not only did I work full-time, I also worked part-time as a bartender.”

But even though she held more than one job while in school, Jennifer still graduated with about $50,000 in student loan debt. Today, after 13 years of making payments and one eight-month deferment period while she was out of work, Jennifer still owes about $28,000.

There’s no other way to spin it: for Millennials and the generations that come after us, paying your own way through school means paying off your education debt throughout your working life. As Jennifer told me, “it’s a weight that never goes away.”

So, what happened? Why was higher education so much more affordable for Boomers and Gen X than it is now for Millennials?

To answer this question, let’s dive into the 3 hypotheses for the astonishing rise in tuition costs over recent decades.